For startups raising venture capital in a crisis is much tougher than they were used to. Fewer deals at lower valuations will inevitably lead to a shake-out in the startup industry. However, startups that respond adequately and adapt their business to the new circumstances, may thrive. Not surprisingly, VCs with a vintage year in or around a crisis show generally better returns.

In a crisis, startups need to manage liquidity more than ever. Securing the run-way is the most important short-term objective. Without run-way to survive a crisis there is no future. That said, short-term measures should go hand-in-hand with the prospects of the business post-crisis. Of course, VCs may want help you to overcome short term liquidity challenges. But they will only do so if they believe your startup is best positioned to tap into the structural economical and societal changes of the economy beyond the crisis.

Nonetheless, investment tickets will be smaller and valuations will be lower. This is not good news for start-ups that have been in a steep upward valuation track through multiple investment rounds. Down-rounds or at best flat-rounds are likely to happen. Founders will experience the negative effects of anti-dilution provisions, a one-sided protection clause for VCs against negative effects of lower valuations.

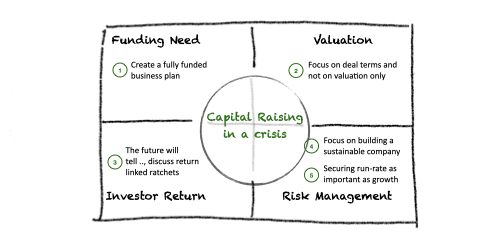

How to structure VC deals in a crisis? In this article, I will describe five ground rules to secure funding in a crisis. Before zooming in on the ground rules, I will quickly go back the Term Sheet Quadrant I published in December 2019. In this article, I looked at a VC deal from four perspectives: funding need, investor return, valuation and risk management. Whereas, in a bull market, the focus is on progressive appreciation of the startup valuation, in a crisis the focus will shift to more granular discussions on funding need, investor returns and risk management.

The Term Sheet Quadrant

The Term Sheet Quadrant consists of four building blocks and a circle in the middle. The edges of the quadrant – outside of the circle – are reserved for the startup needs, the founder objectives and the investor requirements.

The four areas inside the circle are reserved for the the chosen deal terms. In a win-win situation, the deal terms reflect the the startup needs, founder objectives and investor requirements from the perspective of funding need, investor return, valuation and risk management.

Five ground rules to secure funding in a crisis

Regardless we live in a bull market or a crisis, venture capital deals will address to all four building blocks of the Term Sheet Quadrant. However, the balance between the building blocks will be different.

Whereas under normal circumstances, standardised venture funding documentation is easy and fast, they may not provide the right solution in a crisis. No template exists for extraordinary circumstances. Yet, I recommend founders to consider the following five ground rules when raising capital. These ground rules will mitigate some of the key risk areas for the startup and the investor whilst keeping the option to accelerate and – if that plays out well – to re-adjust the deal terms in the future.

I. Create a fully funded business plan

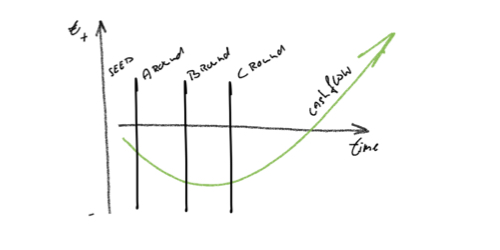

From a risk management perspective, the startup journey is known for taking risks, one after another. In the development phase there is a ‘product risk’. Can we develop a solution that works? After developing a minimal viable product, the startups needs to proof the ‘product-market fit’ and to demonstrate it can realise positive unit economics. This is the second risk category. Once the startup is ready to scale and the organisation needs to scale, the start-up may need to constantly raise capital to accelerate growth.

By building the company – and thus eliminating the risk categories, the startup creates value following the Value Stack: proprietary power, product power, company power and potentially category power. For more information, I recommend reading my article ‘The Value Stack’ on H17.co.

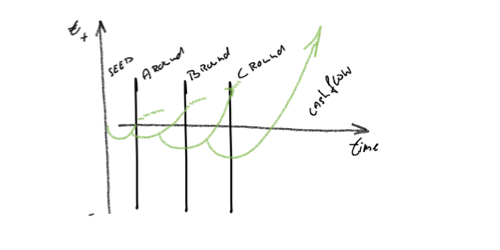

However, as capital raising is typically done through multiple funding rounds, the risk of not being able to secure funding in a future round is called the ‘financing risk’. In a crisis, the financing risk for startups is considerably higher. To mitigate this risk, founders need to create a plan that consists of a bootstrapped plan to extend the run-way with an option to accelerate should more funding become available.

II. Develop an acceleration plan for long term growth

Clearly, the bootstrapped plan does not lead to high growth, therefore an acceleration plan needs to be developed simultaneously. The trigger point to fund the acceleration plan can be agreed upon through well designed milestones as part of the existing round, or through future funding rounds.

III. Focus on building a sustainable company (more than ever)

In the beginning of a crisis, there is a lot of uncertainty about the impact of the crisis and when to expect a recovery of the economy let alone the M&A market. Founders should focus on building a sustainable company and not count on an early exit. That does not mean that no M&A events take place in a crisis. We may even see more acquisitions of scale-ups who’s technology enable an acceleration of the business transformation of corporations.

IV. Focus on deal terms and not on valuation only

In return for smaller tickets and lower valuations and I expect to see more ‘pay to play’ provisions whereby investors are encouraged to participate in follow-on funding rounds to demonstrate commitment (and to avoid losing certain investor rights). It takes two to tango, in good times and bad times …

V. The future will tell ..

Thinking about the future prospects of a business beyond a crisis is not a lineair process. Through developing scenarios about the future outlook, the startup will be able to develop different strategies to accelerate. No one can tell whether a more favourable scenario will materialise over a less favourable scenario. From an investor perspective, it is important to see some down side protection in the deal terms. For the founder team, a ‘non-participating liquidation preference‘ is perceived as more fair than a ‘participating liquidity pref’. In the latter, the investor will first receive in an exit event the invested capital whilst also receiving a pro-rata share in the remaining transaction proceeds. In case a less favourable scenario materialises this could imply that the founders will hardly see any return as most of the proceeds will go to the investors. In a non-participating liquidity preference the investor has to choose between either receiving the invested capital plus a fixed return or to participate in the pro rata distribution of the proceeds following the cap table. No double whammy for the investor.

Equally, founders and investors can agree on a dynamic split of the exit proceeds depending on successes in the future. A common structure is a ‘ratchet’ that is linked to investor return. For example, as from an investor return of more than 3x, the founders will receive a relative higher percentage of the proceeds. In other words, in case of succes, the founders will be compensated for the lower valuation during the crisis.

Summary

The five ground rules in this article suggest founders of a startup to develop simultaneously a bootstrapped plan and an accelerated plan. Through this approach, the bootstrapped plan reduces the risk that the company runs out of cash. The funding for the accelerated plan can be realised through funding tranches based on well designed milestones or alternatively through future financing rounds. Building a sustainable company is foremost the most important objective as an exit may take many more years. To deal with lower valuations, a dynamic equity split (amongst others, a non-participating liquidation preference and a ratchet) can bring more fairness in a deal depending on which scenario will pay out in the future.